Observe:

One evening, while visiting my friends on the outskirts of Albuquerque, the PBS Newshour came on the television. Two pundits from Washington D.C. were debating whether the prisoners at Guantanemo Bay were facing human rights abuses. The subject of waterboarding the detainees came up. One expert claimed it was torture, the other replied that it was not. Neither was confident in their answer.

Perceive:

The twin towers had fallen thousands of miles away, years before and yet the subject of homeland security continued to saturate the news and influence our public consciousness. This was especially true in New Mexico with its air force bases, government secrets, and a desert landscape remarkably similar to Afghanistan.

I had never even heard of waterboarding before that evening. Curious to know more about the practice, I found waterboarding.org, a how-to guide. It is simple to do. To non-lethally simulate the feeling of drowning on the following materials are required:

- water

- washcloth

- inclined surface

I sarcastically suggested to my friends that we should try it. The jokes slowly turned into a dare. A pizza and three beers later, my friends were pointing the camera at me.

Record:

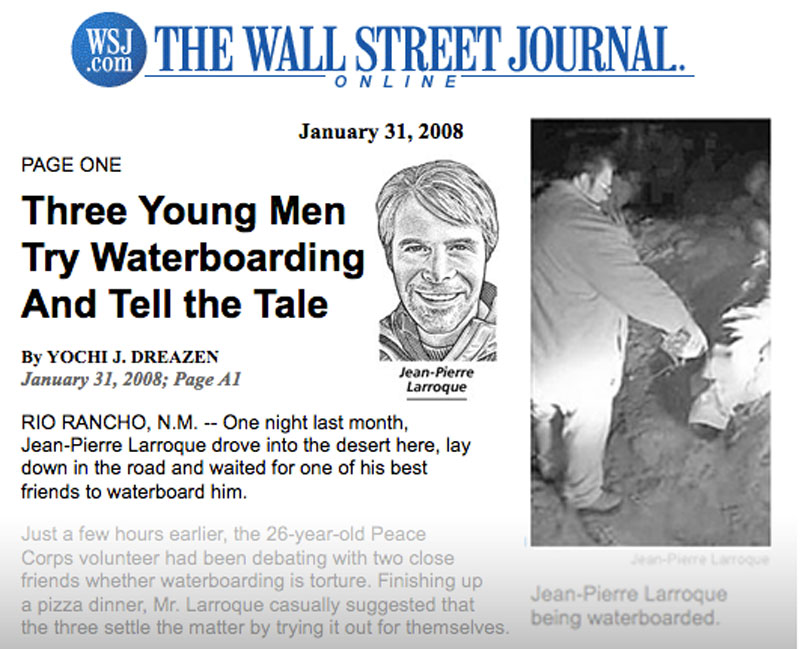

I demonstrated with a washcloth in the dining room what I was going to do. Then we drove out into the desert and one guy poured water on me while the other filmed. The water sucked the breath out of my lungs creating a sensation similar to when you go upside down in a pool and water goes up your nose.

It was December. I shivered from the three gallons of water poured on my face in the freezing desert. I posted the video on YouTube, much to the chagrin of my parents, and then onto this site, mediaforsocialchange.org. I wrote a blog about how I did it with a literature review of all the other waterboarding DIY videos that I found on the Internet. Then I linked to the post in the comments of a Straight Dope column about the subject.

Affect:

A few days later I got an email from someone at the journal, he didn’t say which one, only that he was coming down to Albuquerque.

“Can we meet up?” It read.

I agreed and spent the day with Yochi Dreazen, military correspondent for the Wall Street Journal. Dreazen was writing an article of about how young people in the United States were experimenting with waterboarding and how these experiments were creating a sub-culture on social media. Soon enough, he asked me if I thought it was torture.

I described to Dreazen the blind panic I experienced as the water sucked the air out of my lungs like a vacuum.

“It doesn’t leave a mark like if someone put a cigarette out on your face, and it’s not going to kill you,” I told Dreazen. “So the question we kept coming back to was whether waterboarding could be torture if it mainly affected your mind. It’s almost like the ideal way of torturing someone. This is torture 2.0.”

A couple of weeks later a pointillism sketch of my face appeared on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

In the media cycle that followed I was featured in Gawker, a right wing AM station, the CBS 10 o’clock news, the Albuquerque Journal, and the Weekly Alibi. I turned down Good Morning America.

Evolve:

Waterboarding myself showed me the power that amateur video and social media can have on public consciousness and policy. Waterboarding is now synonymous with modern day torture. Yet, Gauntanemo is still open and it is unclear if terrorist suspects continue to be subject to extreme rendition. Digital media can create advocacy over the Internet and in the press. However, these tactics must continue to evolve if they are to create lasting social change.