____________________________________

Gaudi and the World Trade Center

Gaudi and the World Trade Center

Time is a funny thing. It’s malleable. You can look back at an event in the past and reinterpret it in present day terms. Post 9-11 it’s not hard to read into the closing paragraphs of E.B. White’s 1948 essay “Here is New York”.

The city, for the first time in its long history, is destructible. A single flight of planes no bigger than a wedge of geese can quickly end this island fantasy, burn the towers, crumble the bridges, turn the underground passages into lethal chambers, cremate the millions. The intimation of mortality is part of New York now; in the sounds of jets overhead, in the black headlines of the latest editions.

All dwellers in cities must live with the stubborn fact of annihilation; in New York the fact is somewhat more concentrated because of the concentration of the city itself, and because, of all targets, New York has a certain clear priority. In the mind of whatever perverted dreamer might loose the lightning, New York must hold a steady, irresistible charm.

When I came to New York shortly after 9-11. I found out about a design that was submitted to the World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition. As the big firms presented models in the Winter Garden one entry was absent from the competition. This architect was far better known and loved than any of the others. Why wasn’t his building on display?

For one thing, he’d been dead for 75 years. In 1908 the Spanish architect Antonio Gaudi designed a skyscraper to be built on the site that is now Ground Zero. It was to be a grand hotel with trading floors for the seven continents of the world. It would be a true world trade center. Unfortunately, Gaudi was struck by a street car and died before he could further realize his idea. The land at the edge of Battery Park sat more or less vacant until Yamisaki decided to build the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

For one thing, he’d been dead for 75 years. In 1908 the Spanish architect Antonio Gaudi designed a skyscraper to be built on the site that is now Ground Zero. It was to be a grand hotel with trading floors for the seven continents of the world. It would be a true world trade center. Unfortunately, Gaudi was struck by a street car and died before he could further realize his idea. The land at the edge of Battery Park sat more or less vacant until Yamisaki decided to build the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

This American patron of Gaudi was an extremely affluent financier who actually owned the land bounded on the north by Vesey Street, on the south by Liberty Street, on the east by Church Street, and on the west by West Street (which later became connected with the West Side Highway).

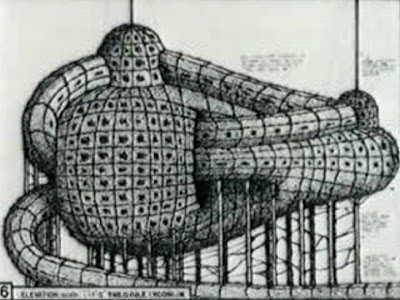

…At first Gaudi was extremely enthusiastic to be part of the American Dream, to such an extent that he felt destined to design the hotel. He made some preliminary sketches of a structure reaching a height of 1016 feet, composed of clustered, catenary-formed parabolic towers of varying heights, grouped together like engaged columns around a central, soaring shaft. But somehow the sketch plans never progressed to the design-development stage…

This is where the story takes on a Roarkian twist straight out of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. Paul Laffoley was fresh out of architecture school when he arrived in New York City. He landed a job with a firm contracted out by Minoru Yamisaki to design the interiors of the World Trade Center. Laffoley spoke out and proposed to build bridges across each of the twin towers to add structural integrity. He was promptly fired. Yamisaki didn’t want anything to disturb “the prism purity” of the “vibrant visual space”.

If Laffoley’s ideas hadn’t been dismissed, the towers would’ve stayed up a lot longer after being hit. That possibly would have given the occupants more time to cross the bridges to safety.

“… No two materials are alike. No two sites on earth are alike. No two buildings have the same purpose. The purpose, the site, the material determine the shape. Nothing can be reasonable or beautiful unless its made by one central idea, and the idea sets every detail. A building is alive, like a man.”

Afterwards, Laffoley became obsessed with structural integrity. He started designing physically alive architecture based on the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Primordial Plant House. Laffoley’s projects started to become more visionary in scope. At one point he theorized on how to build a time machine.

Afterwards, Laffoley became obsessed with structural integrity. He started designing physically alive architecture based on the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Primordial Plant House. Laffoley’s projects started to become more visionary in scope. At one point he theorized on how to build a time machine.

These ideas were incorporated into Laffoley’s reinterpretation of Gaudi’s “Grand Hotel for New York City”. He submitted his plan to the memorial competition and, while it received some attention from NPR and a conspiracy reader, it was largely ignored by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation.

Laffoley wanted to essentially go back in time and erase the devastating events of recent history by implementing Gaudi’s posthumous drawings. The historical building would act as a band-aid over the site, while at the same time usher in a new era of architecture.

Laffoley wanted to essentially go back in time and erase the devastating events of recent history by implementing Gaudi’s posthumous drawings. The historical building would act as a band-aid over the site, while at the same time usher in a new era of architecture.

To those who don’t believe Gaudi isn’t American enough to foot the bill for the World Trade Center memorial, I’d like to reiterate that a Japanese architect designed the original twin towers. Not far away there is a statue out in the harbor sculpted by a Frenchman. The Statue of Liberty is probably the most American of icons. She is an anthem to a defining moment in our immigrant heritage. If Lady Liberty is a symbol that grew into our notion of the American Dream, then the September 11th memorial calls for a monument of equal scale.

About the Movie

This video is an excerpt from a feature length documentary I made on Paul Laffoley called “The Mad One”. The process took two years. It started after I told filmmaker Susan Steinberg about the NPR story and she suggested I cold call Laffoley. Steinberg was a tremendous help in producing the interview portions of this film. In those days I used to work at what is now Three One Design in Times Square making digibeta dubs for MTV and Nickelodeon producers across the street. In the evenings I’d stay late at the office and teach myself After Effects. That’s how the animations came about. My pal Sean “Friday” Barry at Skinnyman did all the sound design. All the music is original and comes from my musician friends Matt Walker, Zsolt, and Dave Baron. In the end this movie happened because of Laffoley. On days off I’d take the Chinatown bus up from New York to hang out with him at The Boston Visionary Cell, his one man think-tank. I sat in Laffoley’s studio as he worked on a painting and he’d give me his take on the universe. Afterward he’d take me out for Eggplant Parmesan.

You can watch “The Mad One” in its entirety below.