Neopatrimonialism and Dominant Party Stability:

The 2011 Ugandan Elections

A video recently uploaded to youtube features the Ugandan president, Yoweri Museveni, at a conference podium addressing an audience.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S7ZZKPxsGDo&fs=1&hl=en_US]

“I can even give you some rap myself nowadays,” Museveni says (DjDinTV, 2010). A samba-esque organ note cuts through xylophone beats and the president starts rapping, in Runyankole, the verses to a folk story that describes the methods for obtaining development.

The stick I cut strayed into Igara where Ntambiko reigns. Ntambiko gave me a knife which I gave to millet harvesters, who gave me millet, that I gave to a hen, which gave me an egg, that I gave to children who gave me a monkey that I gave to the king, who gave me a cow that I used to marry my wife. (DjDinTV)

Museveni is not really rapping the parable but the video is edited to look that way. The music has been added and cuts have been spliced into the film that makes the president look like he’s bobbing to the beat. As Museveni’s song progresses, the bartering sequence becomes rather unfair. A whole monkey is traded by the children to the narrator in return for one single egg. The president goes on to admit that he doesn’t really understand Uganda’s youth demographic.

“Today these young people have taught me about this rap,” Museveni says in between verses. “I was not following what they were saying.”

The chorus of the song is a jingly line edited over and over so that it takes on the tone of a broken record.

“You want another rap?” (x 4) the president asks. The video is cut in a way that Museveni says the line while repeatedly wiping his nose on the sleeve of his jacket.

“Yee sebbo!” The crowd cheers back in a call and response.

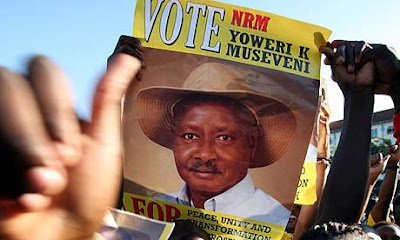

In earlier versions of the music video images of the distraught looking presidential opponent Kizza Besigye were intercut during the chorus between graphics reading. “Nedda Ssebo.” However in the official version, the song changes its tune. One reason might be the 2011 Ugandan elections. You Want Another Rap has become the official song for Museveni’s campaign against Besigye.

Introduction

Most observers, domestically and internationally, believe that Yoweri Museveni will win the 2011 election. Museveni has remained the incumbent for the last three elections, amending the Ugandan constitution to ban term limits in the process. He has ruled the country for 24 years and has no intention of stepping down. The president has brought stability, development, and foreign investment to a small East African country plagued by years of ethnic violence and political turmoil since its 1962 independence from Great Britain. However, this has been at the expense of limited public participation in the creation and shaping of the government.

Will Museveni actually win the 2011 election? Understanding how he has obtained and sustained power can help to answer that question. Museveni transitioned from a guerilla rebel to a foreign donor favorite through electoral engineering. Despite the promotion of multiparty democracy, the president has remained classically neopatrimonial through a patronage scheme that puts foreign aid into the hands of Uganda’s elites. Weak opposition and dominant party stability has kept Museveni strong over the years. However, there are cracks in the system. The effects of corruption has created vulnerability in the regime and soured relations between international donors, ethnic groups and the youth population.

Rise of the Military Elite

Yoweri Museveni came to power in 1986 as the victor of a guerilla war that took place in the Luwero Triangle of Uganda.. The conflict started when Museveni claimed that the previous president, Milton Obote of the Uganda People’s Congress party, had rigged the 1980 election (Ngoga, 1997). While out in the bush, Museveni and his fellow soldiers drafted a 10 Point plan to serve as the governing rules of the new Uganda. These stressed a state governed by a democracy impartial to ethnicity (Museveni, 2000). Future Ugandan politics were intended to be based on what Benjamin Reilly has called a centripetal system that is focus competition at the moderate centre as a way to deal with tribal cleavages.

The most common approach to the engineering of parties and party systems in conflict-prone societies is to introduce regulations which govern their formation, registration, and behaviour. Such regulations may ban ethnic parties outright; make it difficult for small or regionally-based parties to be registered; or require parties to demonstrate a cross-regional or cross-ethnic composition as a pre-condition for competing in elections. (Reilly, 2006)

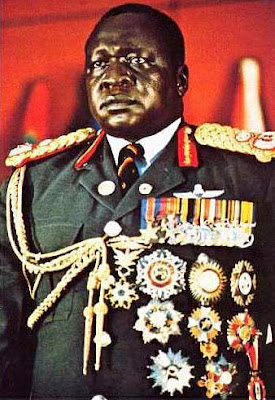

Museveni came to power on the No-Party (or single party) ticket. Prior to this, politics in Uganda featured a complex inter-weaving of ethnic and party politics, with parties mobilizing votes on the basis of ethnicity, region, and religion. The instability that this created was widely seen as having led to the Idi Amin dictatorship in the 1970s (Reilly, 2006). Amin was an example of a personal dictator. His power was so concentrated that it became synonymous with the personal fate of the supreme leader (Bratton & Van de Walle, 1994). This created a neopatrimonial regime along ethnic cleavages that Amin would have ruled indefinitely if the Tanzanians hadn’t exiled him from his country in 1979. Museveni stressed the need for democracy when he became president in1986, but Uganda’s past haunted the structure of its politics. “Institutional characteristics of preexisting political regimes impart structure to the dynamics, and to a lesser extent the outcomes, of political transitions. Regime type provides the context in which contingent factors play themselves out” (Bratton & Van de Wall, 1994).

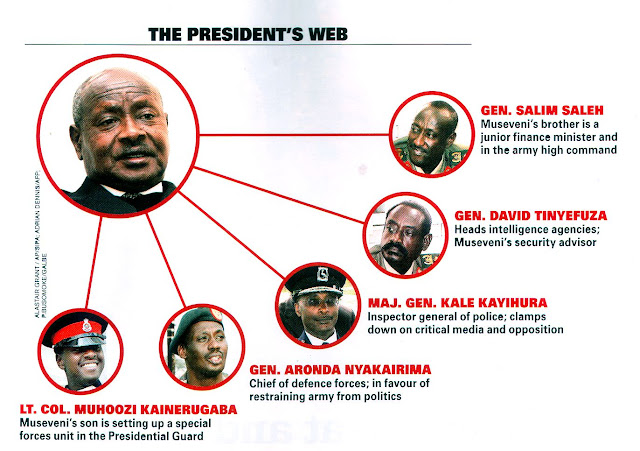

Despite their wishes to create a democracy, Museveni’s National Resistance Movement was a military oligarchy that come to power by force and thus undermined its legitimacy to democratically govern. Power shifted hands between the factions of Ugandan elites, but the underlining character of authoritarianism remained (Bratton & Van de Wall, 1994).

Yet Museveni stabilized the country and economic development quickly began to grow with help from the international community. Uganda had enthusiastically embraced foreign development through structural adjustment programs that opened up a symbiotic relationship of trade, aid, and strategy with the West. Foreign interests expressed enthusiasm for Uganda (Joseph, 1999), but claimed that its single party politics was not a real democracy. Museveni responded with reservations, fearing other parties would reopen scars of tribal conflict. However, “elections are, and meant to be, polarizing; they seek to highlight social choice” (Reynolds & Sisk, 1998 cited in Reilly & Reynolds, 2000). The international community urged Museveni to allow multiparty candidates into the next presidential election. Museveni hesitantly agreed.

Museveni’s worries were understandable. In the early nineties multiparty democracy led to violence along tribal cleavages amongst Uganda’s neighbors. When foreign donors withdrew $1 billion in foreign aid to make Daniel arap Moi agree to hold multiparty elections in Kenya, tribal violence erupted at the polls (Roessler, 2005). Likewise, calls for Rwanda to adopt democratic politics catalyzed the country’s genocide by creating a growing distrust amongst the ruling Hutus that eventually led to the deterioration of ethnic relations. However, in that case, foreign aid actually increased as Habyarimana’s paranoid grew. “In Rwanda the donor community played right into the hands of Habyarimana’s regime; the Rwandan government secured an increase in foreign assistance in the early 1990s as the donors feared that the ethnic violence might spill out of control and destabilize the region” (Roessler, 2005).

While donors have influenced East African politics in the past, they didn’t intervene much after Museveni allowed other candidates to run against him during the No Party elections of 1996. Afterwards, he retained his incumbency. No one contested that the President was reelected after serving ten consecutive years in office. Nor did anyone remember that when Museveni ushered in the new African guard in 1986 he declared that the “problem of Africa in general and Uganda in particular is not the people but leaders who want to overstay in power.” (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010).

In 2005 Museveni agreed to the introduction of multiparty politics, but he managed to amend the constitution to allow presidents to stand for a third elected term. According to Roger Tangri and Andrew Mwenda, he sacked those in government who opposed the change and used political manipulation, bribery, and patronage to push the amendment through parliament in 2006. In the election that year Museveni, who was backed by state military and security services, defeated the rival candidate Kizza Besigye (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010).

Besigye cried foul on the grounds of vote rigging and took the matter to the Supreme Court. The Court agreed with Besigye that there was in fact tampering, but judged that it did not effect the overall results or validity of the election. Allegedly, top political leaders told judges that if they didn’t recognize the election results a military takeover would occur (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010). As the 2011 election approaches, Museveni is preparing to run again. He has used his military and executive power to stay in control for 24 years.

Neopatrimonialism

Despite, Museveni’s promises of term limits and the development of a parliamentary democracy, he is convinced that he cannot step down from his presidency. Like many African states, neopatrimonialism is a strong influence on Ugandan politics. In general, African political regimes are distinctly noncorporatist and “reflect their own peculiar histories, which even during the postcolonial period, may encompass shifts from one regime variant to another” (Bratton & Van de Walle, 1994).

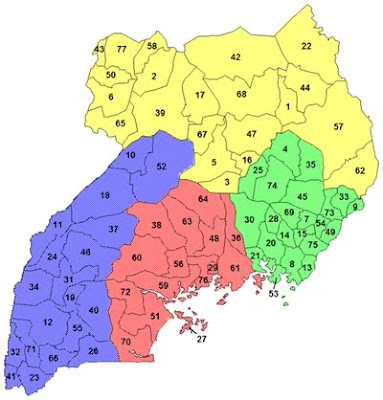

In Western-styled democracy leaders of the United States are elected by individuals to serve as representatives of a federal nation. Museveni has always maintained, especially through his No-Party campaigns, that Uganda is a unified country. This is hardly the case. British colonialists arbitrarily carved up the country’s borders in the 1800s and today a population of eleven major tribes who speak 45 identifiable languages occupy a small swath of land the size of the state of Oregon (Lewis, 2009; CIA, 2010). Traditional African law is pluralistic in nature and during elections communities will tend to vote for a leader that will help their specific locale rather than promote the ideals of the overall nation (Hyden, 1999).

To reduce the potential for ethnic tension, Museveni claims to have subscribed to the centripetal democracy that keeps politics at the center (Reilly, 2006). However, this strategy has never been fully realized in practice. Ugandans have never really chosen their president because he came to power as a military oligarch. Despite the population’s particular tribal allegiances, they have no choice but to back the current Museveni. The traditional, pluralist tendencies are still present, but the president has become the sole patron who decides which communities get resources. Therefore, it is in every local community’s interest to join the NRM.

Museveni, like Amin, has become synonymous with Ugandan power. The identity politics that he embodies does not give him many incentives to step down. Museveni believes that his leadership was detrimental in bringing order and stability to Uganda and that only he possesses the guiding vision for the country’s continued growth. Personally, he has amassed great wealth and power in a region of Sub-Sahara Africa where resources are scarce. Finally he believes that his safety is at risk. If he were to relieve power, he would have to go into exile because he’d be vulnerable to the opponents that he has repressed over the last quarter century (Mwenda, 2007).

Museveni came to power through control of the military, but holds a grip on society through his patronage. For this to be sustained resources are needed. Museveni actively participates in development reform through foreign partnerships with the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and Western governments. They showcase Uganda as one of Africa’s most successful economic reformers. Mwenda believes that their funding just reinforces an authoritarian regime.

The worst obstacle to democratic development in Uganda has been the personalization of the state. Arms and money are essential to this malign process. The arms belong to the military and security services, which the regime deploys selectively in order to suppress dissent. The money sluices through a massive patronage machine that Museveni uses to recruit support, reward loyalty, and buy off actual and potential opponents. (Mwenda, 2007)

Museveni cooperates with the policies of Western interests and the donor community continues to give, focusing on his achievements rather than blemishes. The only time there has been a real cry of concern was when international institutions and governments called for Uganda’s transition from single-party to multiparty government shortly before the 2006 elections (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010). Foreign interests must have approved the legitimacy of the change because in 2007 Uganda was invited to host the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) presided over by Queen Elizabeth II.

Thus, Museveni has the resources of the industrial world at his disposal without much accountability to his own patrons from the West. When he makes a suggestion he is usually met with a consensus of agreement. As Uganda’s structural adjustment programs were being assessed, Museveni argued that the existing civil service was inept in moving development forward (Mwenda, 2007). The international community agreed. To reform this Museveni set up a semi-autonomous body called the Ugandan Revenue Authority. By 2003, donor support created 95 government agencies whose budget allocations grew 30 percent every year (Mwenda, 2007). This changed the district and municipal landscape of Uganda. Local governments rely on 95 percent of their budgets from national ministries in Kampala, the capital, that in turn receive half of their own budgets from foreign aid. To tap into the system, local municipalities subdivided the 33 Ugandan districts that were in place in 1990 into 81 autonomous new ones by 2003 (Mwenda, 2007).

In theory, the creation of new autonomous districts could create a more representational allocation of foreign aid to a broader range of groups. Civil servants at the local level write proposals to be awarded by ministries at the national level. However, they are set up in Uganda so that “the project’s main benefits go to the staffers in the form of salaries, allowances, cars, travel, and per-diems” (Mwenda, 2007). Leaders occupy bureaucratic offices less to perform public service than to acquire personal wealth and status. To maximize their earnings, the bureaucracy of the government is increased. The remaining foreign aid flows at a tiny trickle by the time it is received by the intended recipients of social welfare programs. This rational actor approach fits Bratton’s and Van de Walle’s definition of patronage.

The essence of neoptrimonialism is the award by public officials of personal favors, both within the state (notably public sector jobs) and in society (for instance, licenses, contracts, and projects). In return for material rewards, clients mobilize political support and refer all decisions upward as a mark of deference to patrons. (Bratton and Van de Walle, 1994)

Foreign aid has allowed Museveni to integrate huge sections of the elite class into the government’s patronage network. This redirection of funds requires even more foreign aid to get the job done (Mwenda, 2007). While the elite class has benefited and grown from aid money, most of the population, notably the middle and lower, agrarian classes, have not. Unable to fight back, they choose to exit the system. The middle class has sought exile in other countries. The agrarian class has moved towards subsistence agriculture and trade within the informal economy (Mwenda, 2007).

Dominant Party Stability

In Uganda, the NRM has remained the dominant party for 24 years. Single party rule is common in developing countries when there is weak mobilization during an independence movement. One party rises and dominates power, but still keeps the formalities and symbols of a democratic regime (Barnes, 2010). Oppositions can’t mobilize because the elites have oriented themselves to the party in power to survive.

When there is an opposition it usually comes from a de-facto within the dominant party as in the case of Kizza Besigye. As Museveni’s personal physician, Besigye was very close to the leader during the bush war. In the regime’s early days Besigye was a key player, as the secretary of state, but by the 2001 elections, Besigye had left his government post to run as the only realistic candidate in opposition to Museveni’s No Party politics (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010). Despite calls of a rigged election Museveni held onto the incumbency and had Besigye arrested on charges of treason. Besigye was forced into exile abroad until he returned to Uganda in 2005 to run in the 2006 elections. He was once again detained on counts of treason and charged with rape, but the charges did not stick and Besigye was quickly released from prison. However, the military continued to file appeals against Besigye’s freedom (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010). Most recently, the state has dismissed all charges against Besigye as he runs yet again against Museveni in the 2011 elections (BBC, 2010).

It could be inferred that the Ugandan government wants to be seen favorably by foreign election observers, but this is probably not their most pressing concern. Over the years Museveni has realized that oppositions can’t override the hegemony of the dominant party. Even when they act out of frustration and take extreme measures like violence, these disruptions are superficial (Barnes, 2010). Stability remains because Museveni has chosen a centripetal system of governance that keeps him in the center.

“The strategy of the dominant party vis-a-vis other parties in the system thus has two principal goals; to keep the party near the center where the action is, and to mobilize and rebuff segments of the population selectively in relation to the needs and absorptive capacity of the party. In the development of this strategy the party benefits from its symbiotic relationship with the society in that its dominance insures it a major role in determining where the center is. Moreover, its orientation toward power encourages it to move with long term shifts in public opinion regardless of its ideology.” (Barnes, 2010)

Dominant parties are constricted in their maneuvering by their historical, ideological, and organizational obligations, but overall the system works well for Museveni because these limitations are flexible. “Like the signs that say ‘Police Lines. Do not cross,’ the boundaries may be moved by authorities,” says Samuel Barnes (2010). If Museveni is ever gets in a pinch he can always change the rules of the game so that the outcome is in his favor.

In light of the recent developments of Besigye’s dropped charges and his reemergence into the political arena, Museveni could care less. His party personally appoints the members of the electoral commission. Already, the opposition has called foul play, but because of their weak political standing, they are forced to comply with the national rules and regulations (Assimwe, 2010). Political moves like these by Museveni are visibly clumsy, yet the international donors and a surprising number of constituents that benefit from the NRM’s patronage still align themselves with Museveni. “Yes, he’s a dictator,” they commonly chuckle. “But Uganda’s had worst.”

Most of Museveni supporters sympathize with what Samuel Barnes calls an “old woman’s party” approach to domination in politics. Barnes claims that this is not a pejorative description, although he continues by saying old women “can be difficult, and at times, their attention can be stifling.” However, he goes on to describe more positive aspects. An elderly woman can also be characterized by her motherly concern and tender loving care. In the political realm, these traits are depicted by years of stability, experience, and wisdom (Barnes, 2010). Authoritarianism is not participatory, but it can offer a security that a weak and emerging multiparty democracy cannot.

Dominant Power Instability

Most of the literature agrees with Barnes that dominant parties like the NRM are ironclad and few foresee regime collapse. Mwenda’s analysis hints at a possibility, but he doesn’t believe it is a strong one. One obvious weakness in Museveni’s regime, however, is its dependence on foreign aid. Money that is earmarked for social welfare is redistributed to private elites who in turn reinforce a neopatrimonial machine. Over the last few years Uganda has become sloppy. Donors are aware of the levels of corruption “at the highest levels such as a government audit showing that some 60% of CHOGM expenditure could not be accounted for” (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010).

Foreign organizations have maintained a cordial relationship with Ugandan institutions for their own interests in the region, but some see their contributions as futile and are beginning to pull out. The Presidential Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) program run by the American government has reduced funding this year for the distribution of ARV medication to Ugandan HIV/AIDS patients citing corruption as a major reason (McNeil, 2010, May 9). This will have a devastating effect on a huge population of mostly subsistence farmers who depend on the drugs to stay alive. This loss of foreign aid may not seem so detrimental in light of recent oil discoveries in the North. Museveni’s relatives have been using the state’s military to guard the exploratory area (Mugerwa, 2010, November 11), but petroleum has been known to be a resource curse in developing countries (Ross, 2003).

Also overlooked are ethnic dynamics. Museveni has been quite successful in trivializing the legacies of Obote’s and Amin’s tribal homes in the North first through the guerilla war of 1986 and then the ongoing campaign against the elusive Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) (Berhand, 1997). As he has stayed in power his alliance with the more formidable Baganda tribal majority in the South has also weakened. Museveni began his presidency on good terms with the ethnic group by reinstating the traditional, albeit mostly ceremonial, authority of the Baganda king the Kabaka.

Parliament and heads of state govern from Kampala, the center of the Baganda Kingdom. The Baganda play important roles within the government, but most of the top lieutenants and all of the military elite come from Museveni’s Runyankole homeland in the Southwest (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010). As the years have passed, there has been a falling out between the Kabaka and Museveni who have disputed over the ownership of Baganda tribal land (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010). Tensions reached their threshold in September 2009 when the Kabaka was blocked from attending a government sponsored national youth empowerment day in the newly formed Kayunga district on the border of the Baganda kingdom. This sparked riots between the Baganda and the military (BBC, 2009, September 10).

It’s no coincidence that violence erupted over an event that focused on youth. The country has the second highest population growth in the world and over 50% of Ugandans are under the age of 14 (CIA, 2010). Most aren’t old enough to remember a time when Museveni wasn’t in power and feel disenfranchised. Museveni has created reforms to provide universal primary and secondary education in the country, but the public money allocated has been diverted away from these social welfare programs and into the elite neopatrimonial network. The country’s youngest generations continue to grow up without options for gainful employment, income, or civic participation. The youth population has nothing to lose and little alternative but to resort to violence. Child soldiers have always been a staple in Uganda (Ngoga, 1997). The most recent example is the LRA’s recruitment of children from the marginalized populations of the Acholi in the North (Berhand, 1997). Whatever happens in the 2011 elections, the dominant party’s neopatrimonial structure can weather the storm, but the majority of Ugandans are disillusioned enough with the current leadership to put up a fight.

Conclusion

Museveni will stay put where he has remained for the last 24 years: stubbornly in power. “You don’t just tell the freedom fighter to go like you are chasing a chicken thief out of the house,” he has said (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010). Museveni reminds Ugandans that it was he who liberated them from the draconian regimes of previous leaders like Idi Amin and Milton Obote. In the unstable conditions of the time, power could only be obtained by brute force and it was Museveni’s military oligarchy that thought high enough of its subjects to initiate the social reforms that have brought relative stability to the country. The president believes that he has done Ugandans a favor by amending the constitution to extend his term limits. This is only one indication of an illegitimate regime robed in the façade of democracy. Museveni’s No Party elections are another. Ugandans have had no real choice but to vote for him. As time has past, multiparty elections have been introduced, but only to please international observers, and not in the interest of domestic politics.

Even as he symbolized hope for a democratic Uganda, Museveni has relied on the neopatrimonial system that has characterized most post-colonial African rulers. He has personalized his power and created a machine that increases the bureaucracy of the government to divert funds from international aid into the coffers of his elite supporters. The international community for the most part looks the other way because Museveni entertains the economic and political interests of soft imperialism. The money intended to jump start social welfare programs and alleviate poverty gets eaten up as it trickles down from Kampala. Public goods are not distributed equally and most Ugandans are still stuck in subsistence agriculture. In many parts of the country, Ugandan democracy is indistinguishable from feudalism.

This disempowerment of the masses impedes them from mobilizing against the president. They don’t have the resources to organize themselves efficiently. Museveni has also been wise in keeping his politics moderate. The elites who have the opportunity to overthrow him don’t have much of a reason. If Museveni were disposed the foreign aid that the country has become so dependent on would stop. Even if there were an attempted coup, Museveni’s close relationship with the military would quickly put a stop to the rebellion. Inside Uganda and out, Museveni is affectionately called a dictator; but as far as most people are concerned he’s a relatively benign one.

Yet there are flaws in the current regime that could lead to rupture. International donors have become upset that corruption blocks real progress and some are starting to pull out. Tribal alliances, especially with the Baganda majority, have become compromised over the years. The average Ugandan is young, uneducated, unemployed and frustrated. In the past Ugandans have made their voices heard through violence. Museveni has an impressive military, but Ugandan youth have nothing to lose, but to sacrifice themselves to the cause for change. Even if they don’t actively initiate the revolution themselves, they are vulnerable enough to be recruited by rebels, like Joseph Kony, who can use the effects of Uganda’s backwater development schemes to their advantage.

The issue of what will come of the 2011 election can be seen from two angles. One comes from policymakers and the other from those who live with those policies in practice. “Museveni’s really the only choice,” said, Andrew Chritton, Charge d’ Affaires of the American Embassy when asked about the 2011 election. He went on to say that candidates like Besigye and other parties run only on a one-issue ticket to oust Museveni. The entire scope of their politics is a reaction to the current regime. They have few original opinions on other issues of governance such as the management of the economy or international relations (Chritton, 2009, 23, January). Museveni holds the monopoly on experience and knowledge.

On the other side of the social sphere are the majority of Ugandans who might not be much different from the rioters in 2007’s Kenyan election crisis observed by Japhet Okello, a Luo in his 20s, who lives in Mombasa.

“The politicians weren’t the ones who started fighting out here. It was those boys across over there,” Okello said pointing to a group of teenagers idling on their motorcycles and chewing qat. To Okello, the violence started when unemployed young men saw their country’s loss of faith in the legitimacy of the elections as an opportunity to act out in frustration against the squalor of their living conditions. From Okello’s view the tensions mushroomed from the bottom of society on up.

References

Assimwe , D. (2010, November 02). One million ghost voters cleaned out of register. Daily Monitor.

BBC News. (2009, September 10). King’s supporters riot in uganda. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/8249693.stm

BBC News Africa. (2010, October 10). Uganda court quashes besigye treason charges. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-11524243

Barnes, S. (2010). The dominant party system : a neglected model of democratic stability. The Journal of Politics. 36(3), 592-614.

Berhand, H. (1997). War in Northern Uganda. In C. Clapham (Ed.), African Guerillas (pp. 107-118). Kampala, Uganda: Fountain.

Bratton, M., Van de Walle N. (1994). Neopatrimonial regimes and political transitions in africa. World Politics 46, 453.

Central Intelligence Agency . (2010, November). Cia world fact book, africa:: uganda. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ug.html

Chirtton, Andrew. (2009, 23, January). Personal interview. Masaka, Uganda.

DjDinTV. (Artist). (2010). President museveni rap official video. [Web]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S7ZZKPxsGDo

DjDinTV, . (Artist). (2010). President yoweri museveni you want another rap 2010. [Web]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3BjOHc_R0PA

Hyden, G. (1999). Governance and the reconstitution of political order. In R. Joseph (Ed.), State, Conflict, and Democracy in Africa (pp. 179-198). Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner.

Joseph, R. (1999). The reconfiguration of power in late twentieth-century africa. In R. Joseph (Ed.), State, Conflict, and Democracy in Africa (pp. 57-77). Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner.

Lewis, M. P. (ed.). (2009). Ethnologue: languages of the world, sixteenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

Museveni, Y. (2000). What is africa’s problem?. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minesota.

McNeil, D. G. (2010, May 9) At Front Lines, AIDS War Is Falling Apart New York Times, 1-6.

Mugerwa, Y. (2010, November 11). First family too close to oil sector. Daily Monitor.

Mwenda, A. M. (2007). Personalizing power in uganda. Journal of Democracy, 18(3), 23-37.

Ngoga, P. (1997). Uganda: the national resistance army. In C. Clapham (Ed.), African Guerillas (pp. 91-106). Kampala, Uganda: Fountain.

Okello, Japhet. (2009, July, 14). Personal interview. Mombassa, Kenya.

Reilly, B. (2006). political engineering and party Politics in conflict-prone societies. Democratization, 13(5), 811-827.

Reilly, B., & Reynolds, A. (2000). Electoral systems and conflict in divided societies. In P. Stern & Druckman, D. (Eds.), International Conflict Resoution after the Cold War Washington D.C. National Research Council.

Roessler, P. G. (2010). Donor-induced democratization and the privatization of state Violence in Kenya and Rwanda . Comparative Politics, 37(2), 207-227.

Ross, M. (2003). The natural resource curse: how wealth can make you poor. In I. Bannon (Ed.), Natural Resources and Violent Conflict (pp. 17-42). World Bank Publications.

Tangri, R., & Mwenda, A. (2010). President Museveni and the politics of presidential tenure in Uganda. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 28(1), 31-49.