Searching for Sustainability

Uganda, an East African country about the size of Oregon, has often been referred to as the poster child of Sub-Saharan development, but lately this title has been questioned. In the 1980s, its charismatic president, Yoweri Museveni, led the country out of civil war and created reforms that reduced poverty and disease. However, the leader has been in power for over 25 years and his rule has become increasingly authoritarian. Over the last decade, Uganda’s government has run off of a patronage scheme funded by foreign aid, but rising corruption has made donors withdraw. Museveni now looks for revenue in the early stages of a local oil industry and in partnering with the United States military in the war against terror. This may bring economic prosperity and security to the country, but how the Ugandan people will benefit must be critically examined. For quality of life in Uganda to improve, the current aid flows must be frankly assessed and a grassroots approach must be implemented.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fc_tscUPxMI]

A Success Story

A Success Story

At face value, Uganda is a success story of how, with the help of foreign assistance, a country can rise from the shambles of conflict and disease to develop into a modern state. Thirty years of brutal dictatorship and civil war followed after Uganda’s independence from Great Britain in 1961. On its heels came an HIV/AIDS epidemic and twenty more years of guerilla attacks by the Lord’s Resistance Army. However, Uganda’s charismatic president Yoweri Museveni has done much to achieve stability in the tiny East African country. After leading his National Resistance Army and Movement to victory against Milton Obote in 1986, Museveni called for an end to tribalism and for the promotion of democracy (Mwenda, 2007). He embraced the structural adjustment programs of the World Bank and the IMF and quickly became the darling of the international community who guided him towards holding regular multi-party elections (IMF & IDA, 2010; Joseph, 1999). Museveni’s aggressive campaign against HIV/AIDS led to a 10% drop in the infection rate (AVERT, 2011). In 2009, his soldiers chased Joseph Kony’s LRA out of Uganda and refugees have begun to return to their homes in the North. An estimated 2.5 billion barrels of oil have been discovered in western Uganda that could further infuse revenue into the economy (Moro, 2011). The numbers certainly indicate that there has been progress. Uganda’s poverty rate dropped from 56% in 1993 to 25% in 2010, surpassing the Mlllenium Development Goal of halving poverty by 2015. It has also moved forward in reducing food insecurity, providing universal primary education, and gender parity (World Bank, 2011).

Uganda’s homegrown Rambo.

Donor Dependency and Inflationary Patronage

Museveni said recently that he is tired of relying on foreign aid and is ready for the nation to become independent (Barken, 2011). Yet, all of the country’s achievements are connected to two factors: Presidential Museveni and Uganda’s donor dependency. What looks like progress and stability to the outside is rotten with corruption from within. Museveni has embodied the personal autocratic character of the dictatorial “Big Man.” He believes that he is Uganda’s savior and the country’s stability is his responsibility. His style of rule has left no room for opponents, and the opposition parties are weak and unorganized (Mwenda, 2007). Although Uganda holds regular elections, they are neither free nor fair. Museveni has changed the constitution to extend presidential term limits and won all four times. The president diverted foreign aid to buy patronage and votes.

Opposition leaders and disenchanted citizens are bullied by Museveni’s tight control of the police and the Ugandan People’s Defense Force (Barken, 2011; Tangri & Mwenda, 2010).

All aid flows through Museveni or his appointees and, as a result, essential social services ranging from public education to provision of ARVs have not been delivered to large portions of the population (Mwenda, 2007; McNeil, 2009). The international community has taken notice and pulled back on its funding over the last few years. This has put Museveni in a tough position. The longer he stays in power the more money he has to spend on his patronage. As the budget grows, Uganda’s reserves shrink, and the country has come under strain (Barken, 2011). In addition, inflation has spiked to 30% over recent months after Uganda was advised by the IMF to not restrict food product exports (IMF, 2011). The results have been higher fuel prices, food insecurity, and civil unrest (Kron, 2011).

Thicker than blood.

Striking Oil and Securing the Region

In 2006, 46% of Uganda’s budget came from official development assistance according to the OECD. While Uganda is still the sixth largest recipient of foreign aid in Africa, receiving $1,786m in 2009, aid is currently 26% of the national budget. The drop came after eleven major donors pulled out due to grand corruption (Nyanzi, 2011). Now Museveni must rely on alternative sources of income to uphold the system. His party, the National Resistance Movement, hopes that one solution will come from newly discovered oil. Petroleum is expected to be exported in 2016, but even at these early stages, the natural resource is believed be more of a curse to the country than a blessing. The dealings, conducted between the UK’s Tullow oil, Heritage Oil, Dominion Petroleum, and Museveni’s family, have been marked by their secrecy (Mbabazi, 2010). In October, 2011, Parliament voted in an emergency session to halt the signing of an agreement with the oil companies, citing lack of transparency and accusing Museveni of accepting millions of dollars in bribes (Kron, 2011).

“How’d y’all like to learn some stress positions?”

Museveni has increasingly isolated himself from both essential donors and his own constituents even as inflation skyrockets. However, Uganda has found some relief in partnering with AFRICOM and the United States backed African Union to fight the war against terror. The $200 million in annual military assistance Uganda has received from the US is not merely a handout. Uganda has sent 8,000 peacekeepers to Somalia and and 10,000 security officers to Iraq. “It is thought by some observers that interrogation centers operate within Uganda exercising the Bush Administration’s tactic of extreme rendition,” says a report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Uganda’s participation has also invited terrorist attacks against the country. During the 2010 World Cup, Al Shabab bombed, Kampala, the capital, killing 79 people (Barken, 2011).

[vimeo http://www.vimeo.com/11482321 w=420&h=315]

Bad graphic art gets the presidential seal of approval. A strange case of function following form.

Invisible Children and the Hunt for Joseph Kony

A week after Parliament voted against oil exploration, 100 American military advisors were sent to Uganda to hunt down the Lord’s Resistance Army, a guerrilla group that has not attacked the country since 2005. According to the American Embassy in Kampala, the current deployment of US soldiers will not engage in combat, but instead train local troops and build capacity as part of a long-term strategy (Kron, 2011). While their presence is welcomed by Museveni, much of the appeal for military assistance was generated by the American NGO community. Two human rights organizations, Invisible Children and Resolve, lobbied Congress to end the war in Northern Uganda. Invisible Children, in particular, mobilized 230,000 American youth to rally three times. The charity raised over 4.5 million dollars and used the money to persuade President Obama and Congress to pass The LRA Disarmament and Recovery Act of Northern Uganda. The act calls for the arrest of the LRA’s leader, Joseph Kony and his top commanders (Invisible Children, 2011; Considine Considine, 2011).

Wagging the dog, empowering the youth, and giving no more than half the credit to the locals.

Invisible Children started in 2003 when three American teenagers traveled to Uganda to make a documentary about LRA child soldiers. The group has made several more films on the subject, often staging reenactments with former child soldiers, to build advocacy and document donor-reconstruction projects in Northern Uganda. The NGO’s slick marketing campaign has canvased the Internet and volunteers screen the movies at college campuses. Afterwards, the audience is urged to give donations or purchase a dazzling array of Invisible Children merchandise (Invisible Children, 2011). William Easterly’s Aid Watch blog has ridiculed Invisible Children’s brand of American youth who save disenfranchised Africans (Freschi, 2009). However, the charity’s efforts made the Recovery Act the most widely supported African issue legislation in modern American history (Invisible Children, 2011).

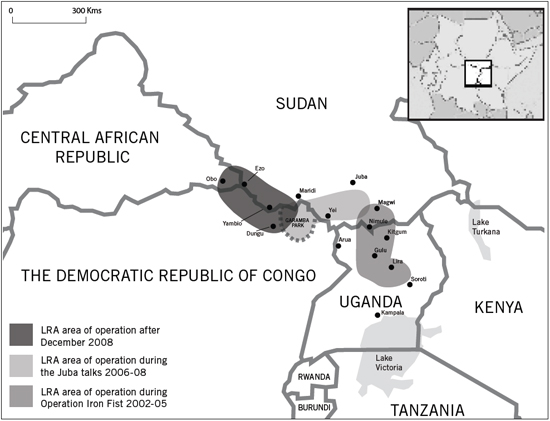

Kony is an easy man to hate. The LRA’s roots go back to the ethnic cleavages of the 1980s civil war. After northeners Milton Obote, a Langi, and Tito Okello, an Acholi, were defeated by Museveni, an Ankole from the west, northern Uganda became marginalized. Factions formed in rebellion (Berhand, 1997). One of these groups, the Lord’s Resistance Army, an Acholi militia supposedly based on the Ten Commandments, routinely raped and pillaged the North; cutting off the lips and noses of villagers as examples of their strength; and most famously abducting children to serve as child soldiers (Chivers, 2010).

A host of international NGOs set up camp in Gulu to provide conflict resolution and humanitarian support for the 1,700,000 internally displaced and families of the 166,000 killed or abducted (Resolve, 2011). Museveni engaged with force and diplomacy, but could never catch the elusive Kony (Pan African News Agency). In 2008’s Operation Lightning Thunder Ugandan, Sudanese, and Congolese forces were backed by the US and struck an LRA stronghold in Garamba National Forest, DRC. The attack eliminated most of the leadership and severely crippled the guerillas. Kony escaped into the Central African Republic where a skeleton crew of insurgents still operates, but since then the LRA has not been a major threat to Uganda (Barken, 2011).

Border security beyond the homeland.

Assisting Regional Stability and Local Instability

Why send American soldiers to Uganda to fight a weak guerilla holed up 1,000 km away in the CAR? The US explicitly states that the mission, has nothing to do with interests in oil or battling Islamic insurgents, but strictly to catch Kony (Kron, 2011). Regardless of the motivation, American presence is strategic for upholding security in the region. If civil war breaks out in the new state of South Sudan an influx of refugees would be devastating to the fledgeling rebuilding process in Uganda where ethnic violence could spread (Barken, 2011). While a stronger UPDF could stabilize Uganda’s northern border, it may create instability on the other side. Uganda has historically been an important gold exporter in the Great Lakes sub-region even though it has no gold resources of its own. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the UPDF entered Eastern DRC to illegally extract minerals. The army’s actions contributed to the fragility of North Kivu provence and was characterized by extreme levels of gender based violence (Ayogu, 2011; Barken, 2011).

The UPDF carpools to Walk to Work Day.

More US military assistance to Uganda could create further instability within the country. Museveni still has tight control of the army that brought him to power. After losing the elections earlier this year, Kizza Besigye, Museveni’s biggest opponent during the elections, organized a “walk to work day” in April to protest rising fuel prices. Museveni responded with force. The military and police were sent to block Besigye from walking, but their presence incited month long riots across the country. Five protesters and two infants were killed from live ammunition, 150 were injured, and 350 were arrested. Besigye himself was wrestled out of his car by police, subdued with pepper spray, and thrown into the back of a pick-up truck. Members of his staff were severely beaten (Kron, 2011). Every election since 2001, Besigye has been harassed and incarcerated on trumped up charges (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010). This year’s military crackdown during post-election protests was not an isolated incident. Museveni clashed with the Bugandan king, the Kabaka, in 2009 (Barken, 2011). The state’s appetite for regular violence has also brought forth allegations of torture and extra-judicial killings. In March, Human Rights Watch released a report that the Rapid Response Unit, a branch of the Ugandan police and an ally of US counterterrorism, tortured sixty Ugandans and killed six (Human Rights Watch, 2011). As Museveni’s economic patronage dwindles and the US heightens military assistance to secure the region, overall democracy, a key to Ugandan stability, weakens.

Special Forces take a cue from the Love Parade.

The need for a more participatory democracy is widely recognized and even promoted through foreign aid (ForeignAssistance.gov, 2011), yet a change in leadership is not likely until 2016, the year of the next presidential election, when Museveni will be 73 years old. Oil will be ready at that date and those vying for power over the resource may knock the dictator from his thrown. Having lived by the sword and in possession of a formidable military, the president will probably not step down peacefully. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, Museveni’s son and head of Uganda’s Special Forces, may take office (Barken, 2011), but any fresh leadership will not come easily. Young Ugandans can’t remember a time without Museveni and older ones are tired of conflict.

What’s Next?

For decades the future of Uganda has been determined by President Museveni and donors from overseas. Recently, the country has been influenced by Western petroleum and security interests. What’s missing from Uganda’s development vision are contributions from the Ugandan people themselves. Museveni dictates politics, foreign banks and NGOs provide social services, oil men negotiate the value of the country’s resources, and the American military defines security priorities. There is a lot of talk about how to create sustainability in Uganda, but not a lot of consideration for homegrown ideas if they don’t come straight from the Big Man at the top.

Still digging for sustainability.

Jeffrey Sachs and others may call for increasing foreign aid (Sachs, 2005), but funds intended for poverty alleviation create government corruption at the highest levels. Other economists such as Paul Collier, correctly identify traps that hinder development within conflict, natural resources, landlocked geography, and bad governance (Collier, 2008). Although in Uganda’s case, Collier’s prescriptions of military intervention, foreign aid, laws and charters, and improved trade policy have been exploited by the leadership and outsiders. Still, foreign aid is necessary to keep Uganda afloat and the $10.1m that the US Government spent on military assistance to Uganda in 2010 is only a fraction in comparison to the $355.6m that it gave for health initiatives the same year. In addition, over $90m was given to promote economic development, democracy, education, humanitarian assistance and the environment (ForeignAssistance.gov, 2011). Yet, when 61% of HIV positive Ugandans don’t have access to essential AIDS drugs (AVERT, 2011); 50% of children are sent to private schools because public institutions don’t function (Barken, 2011); and the military regularly clashes with citizens, aid effectiveness must be questioned.

Progress at the grassroots.

While the leadership becomes increasingly occupied with oil, agriculture is one area of growth that can empower the average Ugandan. Seventy five percent of the population are employed in the farming sector (Feed the Future, 2010) and, aside from an outbreak of hoof and mouth disease in the east, domestic food production is relatively secure (USAID, 2011). USAID programs like Feed the Future invested $50m in 2010 to promote economic productivity, better nutrition, and gender equality in Uganda (Feed the Future, 2010). Even though it does not promise the wealth of oil, improved agriculture can create a surplus that lifts farmers out of subsistence and gives them a taxable income. If the government could capture more revenue, it may rely on foreign aid less, and perhaps be more accountable to its taxpayers (Barken, 2011).

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iMw03PSYebE]

Mobilizing the Resistance.

The Path of the Grasshopper

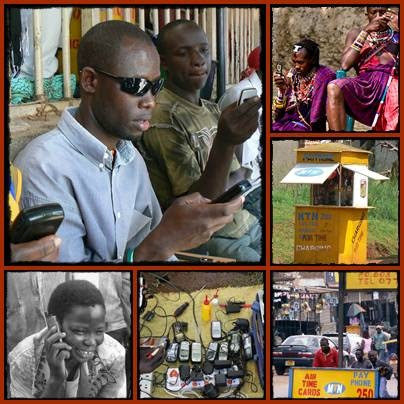

Of course any real development solutions can’t come from this paper. They must be generated from Ugandans. Any large-scale aid scheme given to a corrupt government strapped for cash will instantly be eaten. Funds for agriculture are no exception. William Easterly says that true change must come from searchers, not planners (Easterly, 2006). Sustainable growth in Uganda will never come from proposals of the international community. Ugandans understand the challenges their country faces best and have strongest incentives to overcome them. What really plagues Ugandans is not war, disease, or corruption, but lack of esteem. Neither the president or the international institutions value the opinion of the Ugandan people enough to hand over control. This dynamic may be changing. During the recent protests, Ugandans started looking towards the Arab Spring for inspiration (Mamamdi, 2011). The increased prevalence of mobile phones and social media have given Ugandans a new platform to peacefully congregate off the street and away from the heavy hand of government. Perhaps, solutions to the country’s current predicament will start here.

When life sends you locusts, fry them up with a pinch of salt.

The nsenene is a local grasshopper that is a pest to commercial crops. Recently, entrepreneurs have illegally tapped into power lines along the highways of southern Uganda to plug in bright lights that attract the insects. The grasshoppers are trapped in barrels, fried in oil, and sold at the local market at a premium. The snack becomes more popular every year and nsenene are beginning to be exported to neighboring countries. If international aid organizations decided to eradicate the insects, they would have probably used pesticides. Corruption within the utility company UMEME, makes electricity prohibitively expensive, but at the same time, illegal tapping is harder to enforce (Gatsiounis, 2011). Harvesting nsenene is an example of informal, local ingenuity that has put money into the pockets of Ugandans where foreign assistance and formal governance fails. It is grassroots innovation like this that may ultimately be the path to Ugandan development.

References

AVERT. (2011). Hiv and aids in uganda. Retrieved from http://www.avert.org/aids-uganda.htm

Ayogu, M. (2011). Conflict minerals: An assessment of the dodd-frank act. Brookings Institute, Retrieved from http://www.brookings.edu/opinions/2011/1003_conflict_minerals_ayogu.aspx

Barkan, J. (2011). Uganda: Assessing risks to stability Center for Strategic and International Studies. http://csis.org/publication/uganda

Berhand, H. (1997). War in Northern Uganda. In C. Clapham (Ed.), African Guerillas (pp. 107-118). Kampala, Uganda: Fountain.

Chivers, C. (2010, December 31). ‘all people are the same to god’: An insider’s portrait of joseph kony. New York Times. Retrieved from http://atwar.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/12/31/an-insiders-portrait-of-joseph-kony/

Collier, P. (2008). The bottom billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it . New York: Oxford.

Considine Considine. (2011). Invisible children, inc financial statements 2011 and 2010. Retrieved from Considine Considine Public Accountants website: http://invisiblechildren.com/financials

Easterly, W. (2006, January). Planners vs. searchers in foreign aid. Paper presented at Asian development bank.

Feed the Future. (2010). Strategic review- ugandaUSAID.

Freschi, L. (2009, August 19). How to make an advocacy video about africa [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://aidwatchers.com/2009/08/how-to-make-an-advocacy-video-about-africa/

Gatsiounis, I. (2011, July 5). Insect trappers profit from uganda’s taste for grasshoppers. Retrieved from http://articles.cnn.com/2011-07-05/world/uganda.grasshopper_1_grasshoppers-trappers-rainy-season?_s=PM:WORLD

Human Rights Watch. (2011). Violence instead of vigilance torture and illegal detention by uganda’s rapid response unit . Retrieved from http://www.hrw.org/node/97144

International Monetary Fund. , & International Development Association (2010, March 31). Uganda: National development plan 2010/11-2014/15 joint staff advisory note. Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/external/country/UGA/index.htm

Invisible Children. (2011, October 12). Official statement from invisible children regarding president obama’s action against lra. Retrieved from http://blog.invisiblechildren.com/2011/10/official-statement-from-invisible-children-regarding-president-obamas-action-against-lra/

Joseph, R. (1999). The reconfiguration of power in late twentieth-century africa. In R. Joseph (Ed.), State, Conflict, and Democracy in Africa (pp. 57-77). Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner.

Kron, J. (2011, October 21). Uganda: 2 leaders of protest movement are charged with treason, police say. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/21/world/africa/uganda-2-protest-leaders-are-charged-with-treason.html?emc=tnt&tntemail1=y

Kron, J. (2011, October 17). No combat role for u.s. advisers in uganda, official says. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/18/world/africa/no-combat-role-for-us-advisers-in-uganda-official-says.html?emc=tnt&tntemail1=y

Kron, J. (2011, October 11). Uganda: Parliament votes to halt new oil ventures. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/12/world/africa/in-uganda-parliament-votes-to-halt-new-oil-ventures.html?_r=1&emc=tnt&tntemail1=y

Kron, J. (2011, April 30). Protests in uganda build to angry clashes. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/30/world/africa/30uganda.html?emc=tnt&tntemail1=y

Kron, J. (2011, April 29). Ugandan opposition figure arrested again. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/29/world/africa/29uganda.html?emc=tnt&tntemail1=y

Mamdani, M. (2011, April 24). ‘walk to work’ in a historical light. Daily Monitor

McNeil, D. G. (2010, May 9) At Front Lines, AIDS War Is Falling Apart New York Times, 1-6.

Mbabazi, P. (2010). The emerging oil industry in uganda; a blessing or a curse? . African Research and Resource Forum, 5(2), Retrieved from http://www.arrforum.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=116&Itemid=154

Moro, T. (2011, August 26). Uganda pins hopes on oil. Sun News. Retrieved from http://www.sunnewsnetwork.ca/sunnews/world/archives/2011/08/20110826-104940.html

Mwenda, A. M. (2007). Personalizing power in uganda. Journal of Democracy, 18(3), 23-37.

Nyanzi, P. (2011, April 12). Aid to uganda hits $1.8 trillion in 2010. Daily Monitor. Retrieved from http://www.monitor.co.ug/Business/Business Power/-/688616/1142478/-/o3y76xz/-/index.html

Pan African News Agency. (2006). Uganda: Museveni to boost uganda-lra peace talks in juba. Relief Web, Retrieved from http://reliefweb.int/node/216392

Sachs, J. (2005). The end of poverty: Economic possibilities for our time. New York: Penguin.

Tangri, R., & Mwenda, A. (2010). President Museveni and the politics of presidential tenure in Uganda. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 28(1), 31-49.

USAID. (2011). Uganda food security outlook july to december 2011Famine Early Warning Systems Network.

World Bank. (2011, September). Uganda: Country brief. Retrieved from http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/AFRICAEXT/UGANDAEXTN/0,,menuPK:374871~pagePK:141159~piPK:141110~theSitePK:374864,00.html