Remembering my trip to Berbera in 2016. Names have been changed to protect the innocent.

We drove along the road to Hargeisa past herds of camels, little towns punctuated by whitewashed mosques, and through barren washes that could turn into roaring rivers after a rain. The khat Donny and I chewed stimulated rapid fire conversation in the SUV over the bassy rumblings of the traditional ood music Mo’ played over the stereo. Donny lamented about not being able to go scuba diving or doing other touristy activities during his time on the coast.

“Have you ever heard of Las Geel?” Amit asked, cranking his head around from the front passenger seat to face us.

Donny gave a perplexed expression.

“Have you ever been?” Amit asked me.

“No, not in all the times I have visited Somaliland,” I replied.

We still had the day ahead of us and after more excited chatter decided to make a detour to the place Amit mentioned.

A little further down the highway was a small sign posted by UNESCO indicating the turnoff for a site of cultural importance. Mo’ pulled over and he and Amit got out to speak to a group of men on the side of the road. After some time, they returned to the vehicle. An elderly local got in the second SUV transporting our security team. We could see him greeting them as if they were old acquaintances. Then we took off down a primitive-looking jeep trail; scarred with deep ruts in places and bulging with steep hills in others. Dust billowed from the SUV in front of us carrying our guide. The khat and the road conditions created a queasy euphoria in me as our vehicle struggled around each curve.

At last we arrived at a relatively modern looking building made of cinderblocks. Inside were big photographs that looked old but were actually taken only a few years previously. Somehow they had become bleached by the elements of the desert even though they were mounted in what seemed to be a climate controlled environment. Accompanying the images were descriptions and timelines, mostly in French, that were not much interest to our group. We exited the cool building back out into the glaringly hot midday sun. The guards took sips from tiny plastic water bottles and then we started our hike up a long hill.

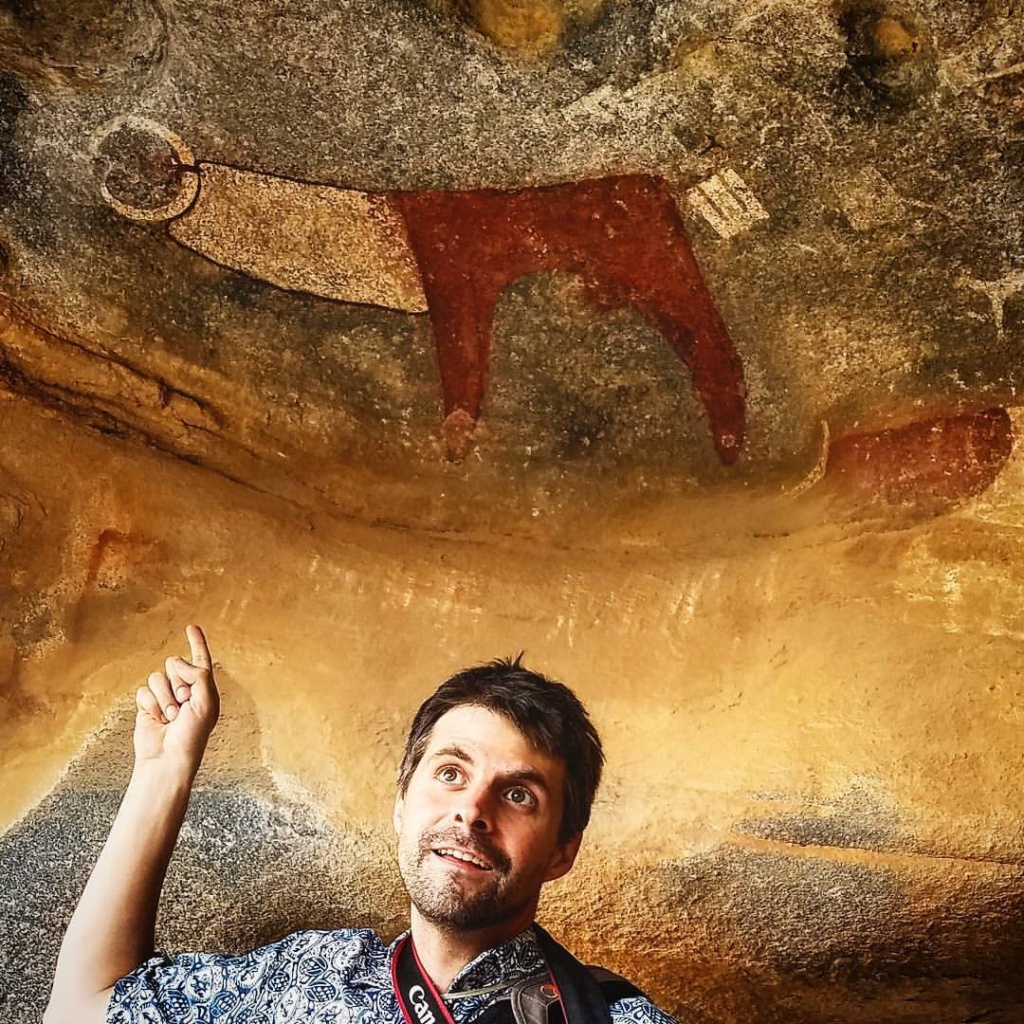

When we got to the top there was more climbing to be done. A big rock formation lay in front of us. We scrambled up to perches where we could balance ourselves on, not yet sure why we had made the detour here on the way back to Hargeisa. Then our guide gestured along the faces of the rock.

As my eyes adjusted I could see a discoloration along the surface. With a little imagination it could be interpreted as some type of weathered symbol. My eyes ran up the side of the sloping wall and there were more, lots more. My vision eventually snapped into focus and I was suddenly surrounded by men and cattle, dogs and camels, and even a giraffe. The pictographs were now brilliantly defined in black and white strokes that contrasted beautifully with the reddish hues on the rocks. The cows were especially a marvel to perceive with their long Ankole-type horns. You might mistake them for a Texas steer were it not for the thick bands that decorated their necks, perhaps some sort of yolk, that looked like Nubian necklaces.

I’ve encountered rock art before in the American Southwest, but these was different. Back home the stuff you see has faded from years and years of exposure to the elements and tourists touching it. In fact, depending on where you are, you’re likely to be politely pushing yourself through a crowd for a glance from a distance since a lot of the good rock art artifacts are cordoned off by fences installed by the park service. These were different. I could get as close as I wanted and each pictograph was brilliantly defined. The art looked brand new to me even though the museum at the bottom of the hill stated they were at least 20,000 years old. I tried to fathom the eons that passed from their creation to the present time as I gazed at the rocks. It made my head spin and I took a slug of water.

Something peculiar happened when we were looking at the cave paintings. The hierarchy and divisions of the group seemed to dissolve. The guards, normally distant to me, became jovial. We gestured to one another like children.

“Check out this cow!”

“Look at that little guy with the spear!”

“What a neat dog! He kind of looks like mine!”

Our guide pointed up a steep face of the rock to indicate there were more images further up. There were some light indentations that could conceivably be used as foot holes, but neither the serikale nor I wanted to test our luck. If one of us slipped climbing them it would be a long way back to the main road, let alone to a hospital. Instead we looked for another way up to the top. One guard found a kind of path that snaked along the side of the rocks and I followed him. After a bit of scrambling we made it to a summit. Looking back we realized that it would be difficult to maneuver over the humps and crags of the formation to get to a place to see the illustrations the guide directed us toward.

I looked around. The rocks we stood on were above the trees. The environment was relatively lush with vegetation compared to the desert below us. Las Geel means “the camels” in Somali. It is thought that the area was named so because it was a watering hole where pastoralists brought their livestock. I looked further along the horizon at the countless other rock formations that punctuated the leafy canopy. How many more prehistoric paintings could be out there on the adjacent hills? It’s not like the Somalis were trying to hide them, but it wasn’t as if anyone, local or internationally, seemed too invested in looking for them either.

I looked over my shoulder and saw the silhouette of my serikale friend on top of another rock. He called to tell me that the group was leaving. Gingerly, I navigated down the boulders, reconvened with my travel companions, and walked back down the path to the SUV. We got in and traveled the remaining stretch of roads back to Hargeisa.